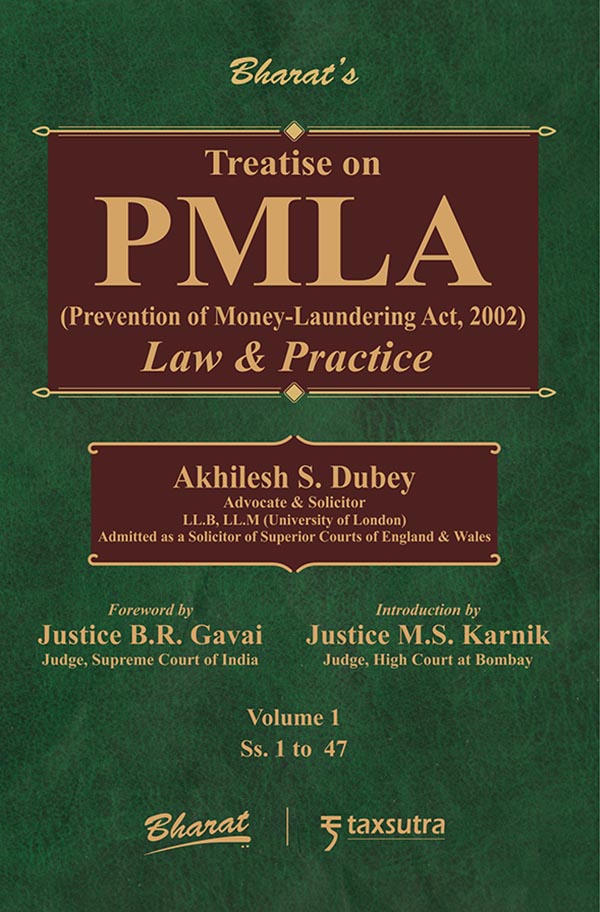

Treatise on PMLA – Law and Practice (Set of 2 Volumes)

Explore the comprehensive ‘Treatise on PMLA – Law and Practice (Set of 2 Volumes)’ authored by Akhilesh S. Dubey and published by Bharat Publishers in its 1st edition of 2023. With ISBN 978-93-94163-84-3 and a whopping 2376 pages, this authoritative work delves deep into the Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, 2002, covering its definitions, offenses, attachment, adjudication, and much more. For a limited time, enjoy a flat 27% discount and free shipping, making it the perfect time to add this invaluable resource to your collection.

CONTENTS

| Content | Page |

|---|---|

| Bharat? | 5 |

| Foreword by B.R. Gavai, Judge Supreme Court of India | 9 |

| Preface to the First Edition | 11 |

| About the Author | 15 |

| About the Book | 17 |

| Acknowledgments | 19 |

| Table of Cases | 31 |

| Introduction to the First Edition by Justice M.S. Karnik, High Court at Bombay | 99 |

| Prologue | 103 |

| Volume 1 : The Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, 2002 | |

| CHAPTER I : Preliminary | |

| 1. Short title, extent and commencement | |

| 2. Definitions | 1 |

| 62 | |

| CHAPTER II : Offence of Money-Laundering | |

| 3. Offence of money-laundering | |

| 4. Punishment for money-laundering | 136 |

| 242 | |

| CHAPTER III : Attachment, Adjudication and Confiscation | |

| 5. Attachment of property involved in money-laundering | |

| 6. Adjudicating Authority, composition, powers, etc. | 296 |

| 7. Staff of Adjudicating Authorities | 399 |

| 8. Adjudication | 433 |

| 9. Vesting of property in Central Government | 434 |

| 10. Management of properties confiscated under this Chapter | 548 |

| 11. Power regarding summons, production of documents and evidence, etc. | 570 |

| 573 | |

| CHAPTER IV: Obligations of Banking Companies, Financial Institutions and Intermediaries. | |

| 11A. Verification of identity by reporting entity | |

| 12. Reporting entity to maintain records | 577 |

| 12A. Access to information | 580 |

| 12AA. Enhanced due diligence | 603 |

| 13. Powers of Director to impose fine | 605 |

| 14. No civil or criminal proceedings against reporting entity, its directors and employees in certain cases | 607 |

| 15. Procedure and manner of furnishing information by reporting entities | 619 |

| 620 | |

| CHAPTER V : Summons, Searches and Seizures, etc. | |

| 16. Power of survey | 622 |

| 17. Search and seizure | 631 |

| 18. Search of persons | 712 |

| 19. Power to arrest | 740 |

| 20. Retention of property | 830 |

| 21. Retention of records | 852 |

| 22. Presumption as to records or property in certain cases | 865 |

| 23. Presumption in inter-connected transactions | 885 |

| 24. Burden of proof | 893 |

| CHAPTER VI: Appellate Tribunal | |

| 25. Appellate Tribunal | 933 |

| 26. Appeals to Appellate Tribunal | 946 |

| 27. Composition, etc., of Appellate Tribunal | 988 |

| 28. Qualifications for appointment | 990 |

| 29. Term of office | 996 |

| 30. Conditions of service | 996 |

| 31. Vacancies | 997 |

| 32. Resignation and removal | 998 |

| 33. Member to act as Chairperson in certain circumstances | 1002 |

| 34. Staff of Appellate Tribunal | 1004 |

| 35. Procedure and powers of Appellate Tribunal | 1005 |

| 36. Distribution of business amongst Benches | 1023 |

| 37. Power of Chairperson to transfer cases | 1026 |

| 38. Decision to be by majority | 1027 |

| 39. Right of appellant to take assistance of authorised representative and of Government to appoint presenting officers | 1032 |

| 40. Members, etc., to be public servants | 1034 |

| 41. Civil court not to have jurisdiction | 1035 |

| 42. Appeal to High Court | 1042 |

| CHAPTER VII: Special Courts | |

| 43. Special Courts | 1074 |

| 44. Offences triable by Special Courts | 1091 |

| 45. Offences to be cognizable and non-bailable | 1130 |

| 46. Application of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 to proceeding before Special Court | 1242 |

| 47. Appeal and revision | 1254 |

| Volume 2 | |

| CHAPTER VIII: Authorities | |

| 48. Authorities under the Act | 1305 |

| 49. Appointment and powers of authorities and other officers | 1306 |

| 50. Powers of authorities regarding summons, production of documents and to give evidence, etc. | 1308 |

| 51. Jurisdiction of authorities | 1335 |

| 52. Power of Central Government to issue directions, etc. | 1337 |

| 53. Empowerment of certain officers | 1339 |

| 54. Certain officers to assist in inquiry, etc. | 1340 |

| CHAPTER IX: Reciprocal arrangement for assistance in certain matters and procedure for attachment and confiscation of property | |

| 55. Definitions | 1348 |

| 56. Agreements with foreign countries | 1349 |

| 57. Letters of request to a contracting state in certain cases | 1350 |

| 58. Assistance to a contracting state in certain cases | 1353 |

| 58A. Special Court to release the property | 1356 |

| 58B. Letter of request of a Contracting State or authority for confiscation or release the property | 1357 |

| 59. Reciprocal arrangements for processes and assistance for transfer of accused persons | 1359 |

| 60. Attachment, seizure and confiscation, etc., of property in a contracting state or India | 1361 |

| 61. Procedure in respect of letter of request | 1373 |

| CHAPTER X: Miscellaneous | |

| 62. Punishment for vexatious search | 1375 |

| 63. Punishment for false information or failure to give information, etc. | 1379 |

| 64. Cognizance of offences | 1394 |

| 65. Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 to apply | 1399 |

| 66. Disclosure of information | 1413 |

| 67. Bar of suits in civil courts | 1416 |

| 68. Notice, etc., not to be invalid on certain grounds | 1439 |

| 69. Recovery of fine or penalty | 1443 |

| 70. Offences by companies | 1446 |

| 71. Act to have overriding effect | 1468 |

| 72. Continuation of proceedings in the event of death or insolvency | 1485 |

| 72A. Inter-ministerial Co-ordination Committee | 1487 |

| 73. Power to make rules | 1489 |

| 74. Rules to be laid before Parliament | 1502 |

| 75. Power to remove difficulties | 1509 |

Informing grounds of arrest: The measured power to arrest under PMLA

In recent rulings, the Supreme Court and the High Courts have criticised the Enforcement Directorate (ED) for its cavalier approach to the rule of law while making arrests under the provisions of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA). The courts lambasted the ED for its high-handedness, asserting that the power to arrest under Section 19 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act is not a wild card to be played at whims and fancies. The courts underscored that due process is not a mere procedural formality but the bedrock of justice. The stern admonitions serve as a clarion call for these agencies, reminding them that the scales of justice cannot be tipped by arbitrary arrests and individuals have the sacrosanct right to fair treatment under the law.

Powers of Arrest under PMLA

Section 19 of the PMLA empowers the Director, Deputy Director, Assistant Director, or any other officer authorised by the Central Government to arrest any person believed guilty of an offence under this Act. However, this power is notl absolute or “untrammelled”. There are certain conditions that must be met before an arrest can be made: 1) Based on material in their possession, the officer must have a reason to believe that the accused is guilty of an offence. This reason must be recorded in writing. 2) The person being arrested must be informed of the grounds for their arrest promptly, and 3) A copy of the arrest order, along with the material in possession, must be forwarded to the adjudicating authority in a sealed envelope.

Informing the Grounds of Arrest and Supplying the Copy of the ECIR

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution stipulates that no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. Article 22(1) stipulates that no person who is arrested shall be detained in custody without being informed, as soon as may be, of the grounds for such arrest, nor shall he be denied the right to consult and to be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice. Section 50(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code says that every police officer arresting a person without a warrant shall forthwith communicate to him full particulars of the offence for which he is arrested.

In the case of Vijay Madanlal Chaudhary v. Union of India (2022 SCC Online SC 920), the Supreme Court ruled that under Section 19(1) of the PMLA, 2002, a person must be informed of the grounds for their arrest as soon as possible, in line with Article 22(1) of the Constitution. The Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR), an internal document of the ED, contains details that, if revealed prematurely, could impact the outcome of the investigation. Therefore, it’s not equivalent to an FIR, and its non-disclosure doesn’t frustrate the purpose of the PMLA. The SC also held that not supplying a copy of the ECIR is not a violation of constitutional rights in as much as informing grounds of arrest is sufficient compliance with the mandate of Article 22(1) of the Constitution.

However, there was a conundrum as to whether the grounds of arrest should be merely informed or communicated to the person arrested. The Delhi High Court, in Moin Akhtar Qureshi v. UOI [2017 SCC Online Del 12108], while rejecting a Petition challenging the detention on non-information of grounds of arrest, observed that Section 19 of the PMLA also uses the expression “informed of the grounds of such arrest” as used in Article 22(1) and does not use the expression “communicate the grounds of such arrest” and the Legislature has consciously used the expression “informed”, which is also used in Article 22(1). The High Court observed that the obligation cast on the ED under section 19(1) is to inform the arrestee “as soon as may be” of the grounds of such arrest as Section 19(1) does not oblige the ED to inform/serve the order of arrest, or the grounds for such arrest to the arrestee simultaneously with his arrest.

Due to this interpretation of Section 19(1) of the PMLA, the ED frequently arrested accused without providing written grounds for the arrest. It often asserted that officers had orally read out the grounds of arrest to the arrested person, a claim that the arrested person regularly contested. This led to disputes over proper compliance, with the situation often becoming a matter of one person’s word against another—the arrested individual versus the ED officer.

Grounds of Arrest are to be communicated in writing

The Supreme Court in Pankaj Bansal v. Union Of India frowned upon this practice of the ED and observed that Article 22(1) of the Constitution provides, inter alia, that arrestee shall be detained in custody without being informed, as soon as may be, of the grounds for such arrest. Being the fundamental right guaranteed to the arrested person, the mode of conveying information of the grounds of arrest must necessarily be meaningful so as to serve the intended purpose. The SC held that a dispute with regards to informing the grounds of arrest could be easily avoided and its consequences can be obviated very simply by furnishing the written grounds of arrest, as recorded by the authorised officer to the arrested person under due acknowledgement, instead of leaving it to the debatable ipse dixit.

The observations made by the apex court, while holding the necessity of furnishing the grounds of arrest in writing are pertinent. It observed that in case of oral reading out voluminous grounds of arrest, it would be well-nigh impossible for the arrested person to record and remember all that they had read or heard being read out for future recall so as to avail legal remedies. More so, a person who has just been arrested would not be in a calm and collected frame of mind and may be utterly incapable of remembering the contents read by or read out to them. The very purpose of this constitutional and statutory protection would be rendered nugatory by permitting the authorities concerned to merely read out or permit reading of the grounds of arrest, irrespective of their length and detail, and claim due compliance with the constitutional requirement under Article 22(1) and the statutory mandate under Section 19(1) of the Act of 2002. The judgment of the Delhi HC in Moin Akhtar Qureshi v. UOI was also considered as bad law.

In summary, while authorities under PMLA do have the power to arrest, this power is not unrestricted. It is bound by certain conditions and procedures to ensure it’s not misused. Communicating grounds for arrest in writing aligns with the principle of the rule of law and constitutional requirements, which ensures a balance between state power and individual rights.

Why India needs a UCC now more than ever

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is a proposed legal framework in India that aims to standardise personal laws for all citizens, irrespective of their religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Presently, personal laws in India are governed by the religious scriptures of various communities and are distinct from public law. These personal laws encompass a range of issues, including marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and maintenance. The UCC seeks to replace these disparate personal laws with a uniform code that applies equally to all citizens.

Implementing UCC in India was first discussed during the drafting of the Indian Constitution in 1946. During the Constituent Assembly debates in the Constituent Assembly, which convened for drafting and framing the Constitution of India, various objections were raised against UCC before it was incorporated through Article 35, which read as: “The State shall endeavour to secure for citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.” During the debate, motions were introduced for including provisos to Article 35, providing that any group, section or community or people shall not be obliged to give up its own personal law in case UCC is enforced and that the personal law of any community, which is guaranteed by the statute, shall not be changed except with the previous approval of the community. However, the UCC was added as Article 35 of the draft Constitution of India and later on incorporated as a part of the Directive Principles of State Policy in part IV of the Constitution of India as Article 44.

Despite the inclusion of the UCC in the Indian Constitution as a directive principle, its implementation was repeatedly deferred by the ruling parties. Citing concerns that the UCC could be divisive and potentially harm the sentiments of minority groups, politicians continually postponed its enactment, claiming that the time is not yet ripe for such a measure. As a result, the UCC languished on the back burner, and its potential was unrealised due to a lack of political will. The BJP has long been a proponent of implementing the UCC, dating back to its origins as the Bhartiya Jan Sangh. Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, a prominent ideologue of the party, famously championed the slogan “Ek Vidhan, Ek Nishan, Ek Pradhan,” which translates to “one country, one constitution, one flag, one head.” As per BJP, this slogan intends to promote national unity and integrity. A massive mandate in the 2014 elections paved the way for BJP to realise its objective. First, Article 370 of the Constitution, which granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir, was abrogated on 5 August 2019, achieving the goal of “Ek Nishan, Ek Pradhan.” Now, with the UCC in the pipeline, the BJP is poised to fulfil its vision of “Ek Vidhan.”

However, the Prime Minister’s endorsement of the UCC has elicited reactions which have now become a political norm in India. As anticipated, supporters of the BJP have championed the UCC, while political opponents have vehemently criticised it without fully comprehending its true intent and historical context. Nonetheless, an outright rejection of a UCC is myopic. Critics of the UCC have argued that PM is attempting to gain an advantage in the 2024 elections by implementing the UCC. However, these objections are based on flimsy grounds, as UCC was a key component of the BJP’s manifesto in the 2019 elections, and the party received a massive mandate from the electorate to implement its policies, including the UCC. Even the debate that it is against minorities is not supported by the history behind incorporating Article 35 of the draft Constitution. Until 1935, the North-West Frontier Province followed Hindu Law, including in matters of succession. In 1939, the Central Legislature abrogated the application of Hindu Law to Muslims in the province and applied Shariat Law. Similarly, in other parts of India, such as the United Provinces, Central Provinces, and Bombay, Muslims were largely governed by Hindu Law until 1937, when the Legislature passed an enactment applying Shariat Law. In regions that now form part of the southern Indian state of Kerala, the Marumakkathayam Law, a matriarchal form of law, applied to both Hindus and Muslims. To overcome this ambiguity in the applicability of personal laws, during the drafting of the Constitution of India, Article 35 proposed a UCC for all citizens but did not mandate its enforcement. The enforcement of UCC was left for future parliaments.

The UCC, a constitutional directive principle, is championed by the founders of contemporary India and epitomises equality. It is not a civil code favouring the majority Hindu population or a law standardising culture, beliefs, or customs. It is an idea whose time has come as envisaged by the framers of our Constitution. Despite being aware that personal laws frequently discriminate against women in matrimonial disputes and inheritance rights, certain political parties are opposing the UCC for the sake of it. A major political party released a statement that reservations to women in Lok Sabha should be given before the implementation of UCC. However, the short-sightedness of such a political statement is evident from the fact that UCC offers India’s female population a chance to reshape the discourse on equality in inheritance and succession rights, which can never be achieved merely by reserving seats for women in Lok Sabha. One strong reason why India needs a UCC now more than ever is that it promotes gender equality and women’s rights. A well-drafted UCC would be a significant step towards achieving gender equality and empowering women in India and further safeguard the equality of all citizens while preserving religious freedom.

Rather than dismissing the UCC at the threshold, opponents must seize this opportunity and participate in discussions on its specifics. The Constituent Assembly, responsible for drafting the Constitution, consisted of members such as B.R. Ambedkar, K.M. Munshi and Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar, who favoured the reformation of the society by adopting UCC. Even the Muslim representatives who wished to retain personal laws never rejected the idea of UCC in toto.

In conclusion, Article 44 in Part IV of the Indian Constitution, which calls for the state to endeavour to secure a UCC for its citizens, represents a constitutional aspiration of the people of India. The implementation of UCC is an issue worthy of conscientious consideration and thoughtful reflection and should be treated as one by recognising its true intent and value rather than opposing it on capricious or ill-informed grounds.

Movie ban calls threaten freedom of expression

India has a rich and diverse culture, where cinema is one of the most popular forms of entertainment and art. However, in recent years, many films have faced censorship, bans, protests, and even violence for depicting sensitive or controversial topics, raising the question: are movie bans in India justified, or are they a violation of the fundamental right to freedom of expression? According to the Constitution of India, Article 19(1)(a) guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression to all citizens., subject to reasonable restrictions. However, this right is often curtailed by various authorities and groups claiming to protect a particular community’s sentiments, religion, caste, region, or ideology.

Reasons for calling movie bans: A PIL was filed before the Calcutta High Court seeking a ban on Aamir Khan’s ‘Laal Singh Chaddha’ as the movie defames the Indian Army and, therefore, it is likely to cause a breach of peace. Recently, YouTube banned “Anthem for Kashmir”, a documentary by filmmaker Sandeep Ravindranath, following a legal complaint by the Government. Similarly, “India: The Modi Question”, a BBC documentary based on PM Modi’s role in the 2002 Gujarat riots, was banned for being “defamatory” and “biased”. Films such as Fire, Water, PK, Padmaavat, The Da Vinci Code and the recent one being “The Kashmir Files” and “The Kerala Story” have faced religious backlash.

Sometimes, vote bank politics plays a vital role in the call for bans on movies. Some films have been banned or opposed for portraying social issues such as caste discrimination, gender inequality, sexual violence, and drug abuse that some sections of society consider taboo or offensive. For example, Bandit Queen, based on the life of Phoolan Devi, a former dacoit, and later an MP who was raped by upper-caste men and took revenge on them, was banned by the Delhi High Court after Phoolan Devi challenged its authenticity. Another film that faced social opposition was “Lipstick Under My Burkha”, which explored the sexual desires and fantasies of four women from different backgrounds. The film was initially denied a certificate by the CBFC as it contains “contagious sexual scenes, abusive words, audio pornography and sensitive touch about a particular section of society”. However, it was later released after an appeal to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal.

Call for a ban based on political ideologies? “The Kerala Story”, a Hindi movie based on the alleged conversion and recruitment of thousands of women from Kerala to ISIS, has faced severe criticism and protests from various political parties and groups in Kerala who claim that the movie is spreading false propaganda and communal hatred. However, some of these same parties and groups have also supported or defended other movies that were banned or opposed by different sections of society for being offensive or controversial. For example, some of the supporters of “The Modi Question”, a BBC documentary that was banned by the Indian government for being defamatory and biased against Prime Minister Narendra Modi, are now demanding a ban on “The Kerala Story” for being defamatory and biased against the Muslim community. This shows the hypocrisy and double standards of people who seek bans on movies based on their own political or ideological preferences rather than respecting filmmakers’ freedom of expression and artistic creativity.

As claimed by the opposition, the phenomenon of bans and boycotts of movies is not a trend set by the current ruling dispensation in India. One can recall the films banned or opposed for depicting political events or personalities deemed sensitive or controversial by the Government or other groups in the past. For example, the Congress government banned “Kissa Kursi Ka”, a political satire on the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi in 1975, and all its prints were burned by Sanjay Gandhi supporters. Another film that faced political censorship was “Black Friday”, based on the 1993 Bombay blasts that followed the communal riots. The CBFC banned the film for three years until the Supreme Court cleared its release in 2007.

Impact of movie bans in India: Movie bans in India stifle the creative expression and artistic vision of filmmakers who want to tell stories that challenge the status quo or reflect the realities of society.

By imposing arbitrary restrictions on what can or cannot be shown on screen, movie bans limit the scope and diversity of cinema as an art form. Movie bans in India also affect the financial viability and profitability of films that have invested much time and money in making the film.

Alternatives: Movie bans in India are a futile and harmful exercise as they often pique the interest and attention of the public for the banned films and attract condemnation and opposition from various sections. Rather than banning films, some feasible alternatives can be explored to deal with the issues or concerns raised by some films without infringing on the right to freedom of expression. One of the alternatives to movie bans is self-regulation by the filmmakers themselves, who can use their artistic freedom with care and sensitivity. Filmmakers can seek advice, input, or feedback from experts, stakeholders, or representatives of the communities or groups represented or impacted by their films and try to depict them fairly and respectfully. Filmmakers can also avoid unnecessary agitation or sensationalism that can harm or offend particular sentiments without contributing value or significance to their films.

Often the filmmakers seem to target the majority community and the upper castes with impunity as nobody raises voice on their behalf, considering them irrelevant for vote bank politics. However, the filmmakers should understand that the political demographics of India have changed. People have started questioning the deliberate targeting of particular communities by filmmakers. Twitter handles such as “gemsofbollywood” have become famous by questioning the intent of these filmmakers. The comments made by Justice N. Nagaresh, while refusing to stay the release of “The Kerala Story”, are relevant to understand the extent to which the filmmakers have taken the liberty to portray the majority community in a bad light. Justice N. Nagaresh orally said, “There are many movies in which Hindu Sanyasis are shown as smugglers and rapists. No one says anything. You may have seen such movies in Hindi and Malayalam. In Kerala, we are so secular. There was a movie where a pujari spit on an idol, and no problem was created. Can you imagine? It is a famous award-winning movie.”

Conclusion: Films should be valued and admired for their artistic quality and social significance rather than silenced or stifled for their imagined or possible harm. Films should be free to challenge, question, or critique the existing norms and systems rather than follow them.

Films should be a catalyst for dialogue, not discord; for understanding, not hatred; for freedom, not fear. At the same time, the filmmakers should be mindful of their responsibility towards the unity and integrity of India and should be sensitive in depicting their characters. At the end of the day, the box office measures a film’s failure or success based on the filmgoers’ choice of content.

National Security Act, 1950: Serves or fails India?

In the wake of farmers’ protest in India in 2021, an organisation called “Waris Punjab De” emerged as a pressure group to champion the rights of Punjab and highlight social issues. The organisation soon deviated from its stated mission and began to undermine the sovereignty and integrity of India by promoting separatism through its leader Amritpal Singh. The Punjab Government cracked down on the organisation and slapped National Security Act, 1980 (NSA) on Amritpal Singh and some of his associates, who were later whisked away to Assam jail to be kept under preventive detention. As in the case of Amritpal Singh, the true intentions, tactics, and consequences of groups acting against the nation’s security and stability often come to light too late, forcing the governments to take swift action. The delay in acting against such anti-nationals is also aggravated by the confusion about the legal measures to be adopted against such separatists, as their statements are defended as free speech.

As Benjamin Franklin once remarked, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” the government, in such a scenario, uses preventive detention as a means to nip anti-national activities in the bud by detaining a person without trial or charge for a limited duration on the suspicion that such person is dangerous to the nation in matters of security, foreign relations, public order, or the essential services and supplies for the community. Preventive detention is not the same as punitive detention, inflicted after a person is found guilty of a crime.

History of Preventive Detention in India—The Defense of India Act 1915, amended during the First World War, enabled the State to preventively detain a citizen. The Government of India Act of 1935 empowered the State to preventively detain a person for reasons connected with external affairs, defence, and discharging functions of the Crown in its relations with the Indian States. The Preventive Detention Act of 1950 was enacted and continued to be in force until the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) was promulgated in 1971. After MISA was repealed in 1977, India did not have any law for preventive detention till 1980 due to massive resentment against the misuse of MISA during the emergency.

National Security Act, 1950—After coming back to power in 1980, the NSA was introduced by Indira Gandhi through the ordinance. NSA empowers the central government and the state governments to preventively detain any person if they are satisfied that such detention is necessary to prevent him a) from acting in any manner prejudicial to the defence of India, the relations of India with foreign powers, or the security of India, or b) from acting in any manner prejudicial to the security of State or from acting in any manner prejudicial to maintaining public order, or from acting in any manner prejudicial to maintenance of supplies and services essential to the community. (Section 3)

Safeguards under NSA— The crucial safeguards concerning the process of preventive detention under NSA include the right of the detainee to make a representation against his detention before an independent advisory board (consisting of three members, the chairman being a member, who is or was a judge of HC), and the provision mandating the advisory board to submit its report to the appropriate within ten weeks of detention to the government. Apart from NSA, the Constitution also grants crucial procedural safeguards under Article 22 in the cases of preventive detention.

Are the safeguards enough—Despite the safeguards, NSA is often criticised for being a draconian and arbitrary law that violates free speech, civil liberties and human rights. The criticism has some valid points. The provisions of the NSA are open to misuse as the grounds for detention are ambiguous and broad; there is scope for unfair trial and denial of due process of law as the detainees are not informed of the evidence or witnesses against them; the detention orders are often based on the subjective and arbitrary judgment of the authority, in the absence of judicial oversight or scrutiny. Although the detention order has to be confirmed or revoked based on the advisory board’s report within 12 weeks from the date of detention, the hollowness of this safeguard is evident because most of the detention orders are upheld. As per the latest statistics released by the National Crime Records Bureau, Preventive detentions in 2021 saw a rise of over 23.7% compared to the year before. Moreover, the immunity provided to Magistrate passing the detention order also leads to abuse.

Misuse of NSA—One cannot forget how MISA was used to suppress dissent and curb political opposition during the emergency years. Nowadays, it has become a competition of sorts between the central and the state governments to impose the NSA at the drop of a hat. The detention of YouTuber Manish Kashyap under the NSA over the allegations of spreading fake news about the attacks on Biharis in TN is the perfect example of misuse of the NSA for political one-upmanship.

The Supreme Court in Rekha v. State of TN (AIR 2011 SCW 2262), while referring to the law laid down in Kamleshwar Ishwar Prasad Patel v. UOI (1995) 2 SCC 51, observed that the history of liberty is the history of procedural safeguards. These procedural safeguards must be zealously watched and enforced by the Court, and their rigour cannot be allowed to be diluted based on the nature of the alleged activities of the detenu. The SC quoted with approval the observation made in a 1981 judgment of Ratan Singh v. State of Punjab that the preventive detention laws afford only a modicum of safeguards to persons detained under them. If freedom and liberty are to have any meaning in our democratic set-up, it is essential that at least those safeguards are not denied to the detenu. Recently, the SC was “quite amazed” that the NSA was imposed on Yusuf Malik, SP leader, in a dispute over revenue dues.

National Security Act 1950 serves or fails India? — NSA is indeed an effective legislation to counter people like Amritpal Singh, who are undermining the idea of India by spreading their skewed version of Indian federalism to promote their secessionist agenda. However, if NSA is misused to target political rivals or suppress dissenting voices, it will weaken the purpose and effect of invoking the NSA and letting India down, as many self-proclaimed liberals are ready to exploit any misuse to label the NSA as oppressive and arbitrary. One may argue that preventive detention is not punitive but preventive.

Behind the Politics of Legislating Fake News

Social media as a community-building tool?

Many of us were drawn to the doors of social media owing to nostalgia. It was a revolution of a kind when Google introduced the popular social networking site “Orkut” in 2004. Social media became an innocuous tool for connecting ourselves to old friends and colleagues. It would not be an exaggeration to say that social media made us pleasantly happy by connecting us. However, as the famous saying goes, everything in excess is opposed to nature. Our addiction to social media dragged us into its evils to the extent that social media, used to connect with old friends, gradually became a tool for picking a quarrel with them owing to political and ideological differences. The transformation of social media from a tool for connecting people to a tool for dividing communities took place in a brief span. Nowadays, spending a few minutes on social media makes us so biased that we start hating people only because they adhere to a different political ideology. The political venom spread on social media may even put Joseph Goebbels to shame. Albeit, reluctantly, every political party admits to using social media to woo followers.

Cambridge Analytica data scandal

The infamous Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal exposed us to the misuse of social media by British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica, which collected personal data belonging to millions of Facebook users without their consent in the 2010s. The data was predominantly used for targeted political advertising and exposed the misuse of social media in disseminating political propaganda.

Dawn of Fake News

Thereafter dawned the era of fake news which consumed our minds, thought processes and social relations through targeted propaganda. Social media platforms like WhatsApp, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and TikTok have become ubiquitous forms of communication to express opinions within society. There are about 692 million active internet users across India as of 2023, out of which about 470.1 million are active social media users, representing about 33.4% of the total population. Due to low data costs and greater reach within the population, social media has evolved into a dangerous weapon for circulating fake news, undermining the country’s security, sovereignty and social fabric. There is no acceptable definition of ‘Fake news’ available to date. Key individuals and institutions involved in research on the subject worldwide avoid using the term ‘fake news’ and instead refer to it as ‘disinformation’. Fake news in India broadly refers to disinformation, misinformation or mal-information.

Perils of Fake News

Fake news has emerged as a towering problem in India, leading to riots in the past. For example, in 2013, a fake video circulated on social media triggered the Muzaffarnagar riots in Uttar Pradesh, which left over 60 dead and thousands displaced. India has a well-organised and carefully-executed operation of spreading disinformation by some vested interests. Recent debates over the authenticity of the videos showing the spate of attacks on north Indians in Tamil Nadu speak volumes regarding chaos caused by fake news. The irony about fake news is the allegation against the self-proclaimed fact-checkers for spreading fake news. Fake news can have serious consequences, and it is essential to take measures to prevent it.

Social media has become a popular medium for sharing information and knowledge, but it is also become a medium for spreading disinformation, hate and propaganda. The Chief Justice of India recently spoke about the dangers of fake news in this digital age at the Ramnath Goenka awards ceremony, where he was the chief guest. He said that fake news poses a severe threat to the independence and impartiality of the press in the current society and that it is the collective responsibility of journalists and other stakeholders to weed out any element of bias or prejudice from the process of reporting events. Fake news can misguide millions of people at once, which will directly contradict the fundamentals of democracy, which form the bedrock of our existence.

Legislations against Fake News

Ministry for Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) introduced the Draft Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules, 2018, to strengthen the regulatory framework to make social media platforms more accountable under the law. Draft Rules 2018 fell under delegated or subordinate legislation framed under the enabling provisions of Section 79 of the I.T. Act, 2000. Subsequently, Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, was promulgated. The I.T. Rules, 2021, as amended from time to time, apart from other things, imposes a legal obligation on intermediaries to make reasonable efforts to prevent users from uploading objectionable content. The provision ensures that the intermediary’s obligation is not a mere formality. The 2022 amendment requires intermediaries to respect the rights guaranteed to users under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Indian Constitution, therefore, includes a reasonable expectation of due diligence, privacy and transparency. To give more teeth to the law, recently, a draft amendment to the I.T. Rules was proposed, which interalia proposed that a) the intermediaries (social media platforms) must remove any information identified as false or fake by the fact-checking unit of the Press Information Bureau (PIB), or any other centrally authorised agency from their platforms, to avoid liability for such content; and b) the self-regulatory bodies [SRB] must evolve a framework to test, verify, and register games such that the sovereignty, integrity, and security of the country are secured.

The proposal to remove any information identified as false or fake by the fact check unit of the Press Information Bureau (PIB), failing which the social media platforms will lose “safe harbour immunity”, which guarantees social media protection against any illegal and false content posted by their users, has now become a bone of contention between the political parties. A tweet dated 7 April 2023 by Sitaram Yechury quoted, “Sweeping powers to the Press Information Bureau to censor the content posted on social media platforms is draconian, anti-democratic and unacceptable. Censorship and democracy cannot coexist.” The said tweet was replied to by Rajeev Chandrasekhar, Union Minister of State for Electronics & Technology, by quoting, “There are NO Sweeping powers – neither is it “draconian”. I.T. rules already have provisions from Oct 2022, which mandate Social Media intermediaries not to carry certain types of content if they are to have legal immunity under Sec79 of the I.T. Act. Social Media Intermediaries will now have to help them a new credible Fact checking unit for all Govt related content. Social Media intermediaries will have the option to follow or disregard fact-checking findings. If they choose to disregard fact-checking, the only consequence is that the department concerned can pursue a legal remedy against social media intermediaries”.

Is the amendment draconian? Politics behind it

In the spirit of democracy, it is essential to debate whether the proposed amendments to I.T. Rules 2021 are draconian and anti-democratic, as quoted by Sitaram Yechury, but at an appropriate stage. However, at this stage, initiating steps to curb fake news is quintessential, as such news can mislead millions of people and undermine our nation’s security, sovereignty and social fabric. The debate over who should be entitled to be a fact-checker is pointless, as some self-proclaimed fact-checkers have already exposed their bias against the government and communities by spreading selective news. Political rivalry should not hinder the government’s initiative to curb the menace of fake news by speculating without even giving it an opportunity to see the light of day.

Disqualification of Rahul Gandhi from Lok Sabha: The road ahead

Rahul Gandhi, a senior leader of the Congress party, was disqualified from Lok Sabha a day after his conviction by a Surat court in a defamation case filed by BJP MLA and former Gujarat minister Purnesh Modi against Gandhi for his remark – “How come all the thieves have Modi as the common surname?” Rahul was convicted under Sections 499 and 500 for defamation of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Section 500 of the IPC extends imprisonment of up to two years, fine, or both as punishment for defamation.

The swift disqualification of Rahul Gandhi from Lok Sabha after being convicted with a maximum sentence of two years under Sections 499 and 500 of IPC has opened the floodgates of political debate regarding the legality and validity of the judgement and misuse of institutions by any ruling dispensation. The quantum of the punishment awarded to Rahul Gandhi, and that too in a case where any particular individual has not been defamed, can indeed be a matter of political as well as legal debate. However, his disqualification from Lok Sabha, pursuant to the conviction, cannot be questioned. Section 8 (3) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RP Act) mandates that “a person convicted of any offence and sentenced to imprisonment for not less than two years other than any offence referred to in sub-section (1) or sub-section (2) shall be disqualified from the date of such conviction and shall continue to be disqualified for a further period of six years since his release.” The plain reading of section 8(3) of the RP Act clarifies that the moment Rahul Gandhi was convicted and sentenced to two years in jail, he was disqualified as an MP. In accordance with Section 8(3), the Lok Sabha Secretariat has correctly released a notification stating March 23rd as the day of disqualification rather than March 24th, the date on which the notification was issued. According to Section 8 (3) of the RP Act, Rahul Gandhi is prohibited from participating in electoral politics until 2031 as he has been convicted. The law specifies that the disqualification will continue for an additional six years after his release. In 2025, when his two-year sentence concludes, the six-year disqualification period will begin.

The law relating to criminal defamation is also well-settled. The Constitutional validity of sections 499 and 500 of IPC, 1860 and section 199 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC, 1973) was assailed in Subramanian Swamy v UOI, Ministry of Law, [2016 (5) SCJ 643]. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the said sections by observing thus: “One cannot be unmindful that right to freedom of speech and expression is a highly valued and cherished right, but the Constitution conceives of reasonable restriction. In that context, criminal defamation, which exists in the form of Sections 499 and 500 Indian Penal Code, is not a restriction on free speech that can be characterized as disproportionate. The right to free speech does not mean a citizen can defame another. The protection of reputation is a fundamental right. It is also a human right. Cumulatively it serves the social interest.” It is a matter of argument before the appellate court whether the law relating to criminal defamation has been correctly applied while granting maximum punishment of two years to Rahul Gandhi while convicting him, but the immediate risk lies elsewhere.

If Rahul Gandhi’s conviction is not suspended or overturned, or if the appellate court does not reduce his sentence, he may be unable to participate in the upcoming general election scheduled for 2024 due to disqualification. The Election Commission now has the technical ability to conduct the by-election for the Wayanad constituency. For Rahul Gandhi to retain his seat in Parliament, he must obtain a court order to stay his conviction. If his conviction is stayed or overturned and a new election has not been conducted in Wayanad, he may be reinstated in Parliament. A reduced sentence would also remove the disqualification, but this will require the appeal to be heard finally, which may not be feasible in a short amount of time.

There is no confusion over the provisions of law governing the disqualification of Rahul Gandhi in as much as the Supreme Court verdict in Lily Thomas Vs Union of India and Ors (2013) implies the disqualification to be immediate upon conviction by striking down Section 8 (4) of the Representation of People Act, 1951, as unconstitutional. The RP Act under Sections 8(1), 8(2), 8(3) provides that if a legislator is convicted of certain offences which are provided in these sections, he/she shall stand disqualified from being a lawmaker. However, sub-section (4) of Section 8 of the Act gave some relaxation to the convicted person by providing that notwithstanding anything in sub-section (1), sub-section (2) or sub-section (3) in Section 8 of the Act, a disqualification under either subsection shall not, in the case of a person who on the date of the conviction is an MP or an MLA, take effect until 3 months have elapsed from that date or, if within that period an appeal or application for revision is brought in respect of the conviction or the sentence, until the court disposes of that appeal or application.

The constitutional validity of Section 8(4) was challenged before the Supreme Court in Lily Thomas v Union of India (2013). The Supreme Court struck down Section 8(4) of the RP Act by holding that Section 8(4) is ultra vires to the constitutional provisions and that the Parliament has exceeded its powers by bringing in Section 8(4). The Supreme Court further observed that the sitting members who have already benefitted from Section 8(4) would not be affected by this judgement. However, if any sitting member of Parliament or state legislature is convicted under subsections 1, 2 and 3 of Section 8, they shall stand disqualified by virtue of the said judgement. Thus, the legality of the disqualification of Rahul Gandhi from Lok Sabha is legally correct.

The road ahead: Rahul Gandhi has to immediately move to the Appellate court and seek a stay of conviction by the Surat court. Though the Supreme Court in Navjot Singh Sidhu v. State of Punjab [(2007) 2 SCC 574] has held that a stay of the order of conviction by an appellate court is an exception to be resorted to in a rare case after the attention of the appellate court is drawn to the consequences which may ensue if the conviction is not stayed. Obtaining a stay of conviction would not be difficult, given the accusations against Rahul Gandhi in the complaint lodged by Purnesh Modi, the magnitude of the sentence issued by the Surat Court, and the potential repercussions if the conviction is not suspended. Since the decision in Rama Narang v. Ramesh Narang, [(1995) 2 SCC 513] by the Supreme Court, it has been well settled that the appellate court has the power, in an appropriate case, to stay the conviction under Section 389 besides suspending the sentence. The power to stay a conviction is by way of an exception. Before it is exercised, the appellate court must be made aware of the consequence which will ensue if the conviction is not stayed. Once the conviction has been stayed by the appellate court, the disqualification under sub-sections (1), (2) and (3) of Section 8 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 will not operate.

Given the lackadaisical approach of Rahul Gandhi’s legal team in defending the defamation case before the Surat court, the path forward is more complicated than it may seem, especially as Rahul Gandhi is legal options are running against time. Thus, if Rahul Gandhi intends to participate in future elections, he must act swiftly to seek a stay of conviction from the appellate court.

Link between judicial delay, corruption is a complex one

The Chief Justice of India’s recent statement on the reluctance of judges in the lower judiciary to grant bail is noteworthy as it highlights a crucial issue of flooding of bail applications before the higher judiciary. The CJI recognised that the reluctance was not due to a lack of understanding or ability, but because of a sense of fear. The CJI’s acknowledgement of the issue is commendable as it indicates a positive step towards addressing the delay in justice delivery. The reluctance of the judges at the lower judiciary in not making impartial decisions due to a sense of fear, alongwith other factors such as frequent adjournments, lack of resources, outdated laws, and a lack of political will to reform the system, delays the judicial process, leading to judicial corruption. The relationship between judicial delay and corruption is a complex and multifaceted one.

This connection is particularly pronounced in India, where a backlog of cases and inefficiencies notoriously bog down the judicial system. A sluggish justice delivery system, characterised by long wait times and slow progress, breeds corruption in several ways. The figures provided by the government concerning pending cases, even without considering the alleged biased independent reports, are startling. According to the National Judicial Data Grid, as of December 2022, there were over 43 million pending cases in the Indian courts. In 2020, India’s ranking in the category of “Enforcing Contracts”, which takes into account the time, cost, and quality of the judicial process, was 163rd, with the time taken to resolve a commercial dispute being approximately 1,445 days. According to data from the law ministry, as of August 2022, there has been a significant improvement in the ranking of India, with a close to 50% reduction in the number of days taken to resolve a dispute.

Specifically, the time taken to resolve a dispute in New Delhi has been reduced to 744 days, and in Mumbai, it has been reduced to 626 days, which is again a commendable effort, but there is a long way to go. The Law Commission of India also shares the concern about the judicial delay and recommended steps to minimize backlog of cases. No doubt the current government and courts are also working towards reducing the backlog, but it’s too little, too late. One of the most obvious ways judicial delays contribute to corruption is through bribes to expedite the process. In a system where cases drag on for years, people are more than willing to pay bribes to ensure that their case is given priority or that a favourable ruling is handed down, leading to a culture of corruption where the only way to get justice is through illegal means.

According to Transparency International India’s report, the key form of corruption prevalent in the judicial sector is predominantly “paying money” to the “court official”. To add to the justice seeker’s misery, money sometimes must be paid to the public prosecutor and even the opponent’s lawyer to speed up the procedure. The judicial delay fuels corruption by creating an environment where the powerful and well-connected can evade accountability. The sluggish and inefficient legal system is acting as a catalyst to those with resources and influence, who use their position to evade prosecution or to have charges against them dropped by delaying the trial.

This has led to a perception that the justice system is tilted in favour of the wealthy and wellconnected, further eroding public trust and fueling corruption. It is a matter of record that most of the bails in huge scams are granted on the ground of “delay in the trial”, while in petty crimes, the bail applications do not even come on board for a hearing. Similarly, in many cases, the accused are acquitted in trials that take place many years after the alleged crime due to a lack of evidence. The impact of judicial delay can be particularly severe for victims and marginalised communities. When justice is delayed, victims cannot access compensation or other forms of relief and are left in a state of uncertainty and vulnerability. There are cases where poor who cannot afford a lawyer languish behind bars during the entire trial period without access to bail. This apathy has further led to a lack of faith in the justice system among these communities. There are countless examples where individuals who could not afford lawyers languished in prison even after serving their sentences, while individuals with influence were able to secure midnight court hearings. The fact that when the justice system is slow and inefficient, it creates opportunities for corrupt practices to take place cannot be countenanced by any argument to the contrary. When cases take a long time to be heard and decided, and the court system is overwhelmed and backlogged, it leads to a lack of accountability and transparency, creating opportunities for corrupt officials to take advantage of the situation and abuse their power. The justice system’s corruption can be immensely reduced by addressing the judicial delay issue.

The issue of judicial delays cannot be addressed by simply making hollow promises. To tackle the issue, it is essential for all stakeholders involved to take action and follow through with their commitments. This includes the government, judiciary, legal profession, civil society, and the media. They must work together to identify the root causes of the delays and implement practical solutions to address them. For example, the government can invest in improving the infrastructure and resources of the court system to reduce overcrowded court dockets. The judiciary can implement court management systems to increase efficiency and reduce delays. The legal profession can work to increase access to justice for disadvantaged groups. Civil society can raise awareness about the issue of judicial delays and advocate for change. The media can report on the issue and hold the stakeholders accountable for their actions. In the backdrop of the statement made by the Chief Justice of India regarding the reluctance of judges in the lower judiciary to grant bail, we must not forget that nobody came in support of erstwhile Justice Pushpa Ganediwala, who was forced to resign from the Bombay High Court as her judgment on POSCO did not go down well. Thus, until there is a genuine intent to eliminate delay in the justice delivery system, any commitment to reduce corruption in the judicial system is nothing but a pipe dream.

Lack of OBC data: A threat to electoral plans of BJP

The Other Backward Classes (OBCs), who play a major role in caste-based politics, are a socially and economically disadvantaged group in India and constitute a significant portion of the country’s population. According to the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data for 2011- 2012, the OBC population in India is estimated to be around 41% of the total population. Additionally, The Indian Government has a criterion of 27% reservation for OBC in all educational institutions and government jobs. This criterion is based on Mandal Commission Report, which the government commissioned in 1980. But the exact percentage of the population of OBC is not readily available as it’s not been collected by the government. Recently, the Allahabad High Court nullified the UP Government’s notification from 5 December 2022, which reserved four mayor seats in the upcoming Urban Local Body Elections. The court held that the notification did not meet the criteria set by the Supreme Court for determining the political backwardness of OBCs to reserve seats for them in local municipal bodies as per the ‘Triple Test’ conditions laid down in Vikas Kishanrao Gawali case. The ‘Triple Test’ criteria of the 2021 judgement provided that a dedicated Commission should conduct a rigorous inquiry into the nature and implications of the backwardness of local bodies within the state, specify the proportion of reservation required for local bodies in light of the Commission’s recommendations and not exceed an aggregate of 50% of the total seats reserved for SCs/STs/OBCs taken together. The High Court ordered the State poll panel to immediately notify the local body elections, stating that it is essential for democratic governance and cannot wait due to the time-consuming task of collecting materials to satisfy the triple test criteria and the municipalities’ term ending on 31 January 2023. The order created a huge uproar leading the opposition to blame the BJP government in UP for taking an ‘anti-OBC’ stance. As the BJP is supported by large number of OBC voters, the UP government quickly responded to the Allahabad High Court’s order. In response, UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath stated that the government will follow the guidelines set by the Supreme Court to implement OBC reservations in urban local body elections. As an immediate measure, the UP government set up a “dedicated OBC Commission” to carry out an inquiry in addition to filing an appeal before the Supreme Court, which is pending hearing by granting time till 31 March 2023 to provide requisite data. The OBC population data is a major concern for the BJP in several states. In 2018, the BJP-governed state of Maharashtra passed the “Socially and Educationally Backward Classes Act, 2018” (‘SEBC Act’) to provide reservations for the Maratha community under the OBC category. The reservation for Marathas was contrary to the 102nd Amendment of the Constitution, which removed the states’ power to add or delete communities in the OBC category. However, the central government supported the SEBC Act despite this inconsistency. The Act was struck down by the Supreme Court on the grounds that it exceeded the 50% reservation threshold and contradicted the 102nd Amendment. The predicament of the central government was evident in their support for the SEBC Act, despite the fact that the 102nd amendment was formalised by themselves, anticipating similar legislation by individual States. To address this challenge and due to political pressure, the 105th Amendment to the Constitution was passed by the Parliament in August 2021, allowing States to establish their own lists of OBCs. It’s important to note that OBC classification is based on social and educational disadvantage, and population figures can change over time, making it difficult to provide exact figures. Determining the population figures for OBCs can be challenging, as the definition of OBCs and criteria used for identifying them vary from state to state and are time-consuming. The first issue arising from the lack of OBC population data occurred when the Maharashtra government decided to proceed with municipal elections in December 2021, reserving seats for OBC candidates using Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) data. The decision of the MVA government was challenged before the Supreme Court, which considered the “triple test” criterion as the centre did not support the SECC data citing “inconsistencies”. The Socio-Economic and Caste Census 2011 was conducted during the 2011 Census of India. The Manmohan Singh government approved the census after discussions in both houses of Parliament in 2010. However, when the data was compiled in 2014, the central government changed, and the incoming central BJP government decided not to make it public. The decision of the central government to deny the state governments the ability to establish their own lists of OBCs by enacting 102nd Amendment on one hand and on the other hand prohibiting the use of SECC data created further confusions. The absence of OBC population data has been a problem in various states, where the reservation of OBC seats in Panchayat and Municipal elections is often disputed and is subject matter of challenge before courts. A challenge to the lack of OBC population data recently led the Madhya Pradesh government to provide statistical data on OBC before Supreme Court for going ahead with local body elections. Similarly, the Gujarat government was, in a way, forced to announce an OBC commission after the State Election Commission called for 10% of OBC seats to be converted to general seats. The 103rd Amendment of 2019 that gave 10% reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) has intensified the issue, as OBC leaders see it as an opportunity to demand OBC reservation beyond the 50% quota limit, similar to the EWS reservation which was upheld by the Supreme Court. It is unclear whether it is a political strategy or confusion on part of respective BJP governments in State and Center. But is evident that the BJP is taking a risky approach, as evidenced by their contradictory positions on various issues related to OBC population data, be it opposing the enumerating of the OBC population in Bihar while in power with Nitish Kumar, or supporting enactments like the Maharashtra SEBC Act, 2018 before the Supreme Court. If the BJP wants to maintain its winning streak, it will need to keep an ear on the ground where the opposition is trying to attract the OBC voters by appealing to their emotions and portraying the BJP as ‘anti-OBC’. The opposition’s political strategy is evident in a decision of Nitish Kumar’s government in Bihar, which proposed a caste census after separating from the BJP, to be completed by May 2023.

Pros and cons of legislating online gaming in India

In recent years, the gaming industry in India has gained unprecedented leverage in the entertainment world. In 2021, almost 50% of the internet users in India played online games, totalling around 433 million out of the 846 million total internet users. Approximately 35% of the population became online gamers in 2021. It is expected that the number of internet users in India will surpass one billion by 2023, and the number of online gaming users in India will increase from 481 million in 2022 to 657 million in 2025. Unfortunately, the regulations governing online gaming in India are unable to keep up with the speed with which online gaming has significantly evolved in recent years. Until recently, even a nodal ministry to regulate online gaming was not designated by the government, leading to dodging the issue of regulating online gaming to respective states under ambiguous provisions, which do not even define online gaming. In India, Public Gambling Act 1867, the Prize Competition Act 1954, certain offences under the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and the Lotteries (Regulation) Act, 1998 “indirectly” regulate the online gaming industry. The word “indirectly” is deliberately used as the law enforcing agencies in India misuse the provisions of these legislations to prevent online gaming under the garb of regulating it. Due to a lack of uniform central legislation to regulate the online gaming industry, agencies erroneously charge online gamers under the provisions of these acts leading to almost zero convictions. Unfortunately, law-enforcement agencies in India believe in the principle of “process is the punishment” to overcome the lacuna or gap in legislation. On the other hand, several States have enacted respective legislations to regulate online gaming and gambling. However, they are ineffective in dealing with the unregulated online gaming industry due to their lack of uniformity. For example, a person playing online chess by paying a token fee in one State of India can be characterised as a criminal in that State, whereas in another State, he will be considered an online athlete (a term used to define online gamers). This inconsistency is not only limited to the legislations enacted by respective States but has pervaded into judicial decisions also. There are umpteen conflicting judgments on the interpretation of the game of skill (which does not fall under gambling) and the game of chance (which falls under gambling). However, as every cloud has a silver lining, the ambiguities and conundrums in regulating online gaming have led to a consensus among various groups, such as State Governments, the online gaming industry, the Law Commission of India, and the Indian government think tank Niti Ayog, on the necessity of legislating a uniform law for regulating online gaming. In recent years, the Government of India has sought to regulate the gaming industry by taking several initiatives. In 2018, the Law Commission of India proposed a central legislation in its report titled “Legal Framework: Gambling and Sports Betting including Cricket in India”. In December 2020, Niti Ayog released a draft report proposing creating a “uniform national level safe harbour framework” for fantasy sports, which would also provide guidelines for determining which games are games of skill. However, Niti Ayog, instead of proposing a central legislation, proposed recognition of a single selfregulatory body for fantasy sports. The government’s seriousness in regulating online gaming is evident from allocating matters related to online gaming to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY). By doing so, the government has designated MEITY as the nodal ministry to regulate online gaming. Against this backdrop, after considering input from various relevant government departments and other stakeholders, MEITY developed draft amendments to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, which were issued under the Information Technology Act, 2000, in January 2023. One of the crucial features of the draft amendments is introducing a self-regulatory structure in the form of a self-regulatory body (SRO) comprising five members from diverse fields, including online gaming, public policy, IT, medicine and psychology. Overall, the draft amendments to the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 represent an attempt to strike a balance between the needs of the online gaming industry and the concerns of society. While some have praised the measures as necessary to protect players and ensure the online gaming industry’s integrity, others have raised concerns about the potential for overregulation and the impact on innovation and entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, the draft amendments are not free from potential drawbacks such as censorship, privacy concerns, economic impact and freedom of expression. However, it would be too early to comment on the same. But the most critical drawback is the lack of distinction between “games of skill” and “games of chance.” The draft rules apply to all online games, regardless of whether they are considered games of skill or chance, as the government is keen on not distinguishing the same in consonance with global practice. Further, the Self-Regulatory Organization (SRO) model for regulating online games may be problematic because requirements for registration are not clear. It is relatively straightforward if registration of an intermediary involves paying a fee, becoming a member, and following rules and regulations that require companies to offer only games of skill. The apprehension is that the SRO under the draft rules may also act like the SRO of other online platforms, such as Over-TheTop (OTT) players, where the SRO only provides registration for a fee and require adherence to specific terms and conditions rather than certifying what content can or cannot be shown on those platforms. Thus, the absence of distinction may lead to unscrupulous elements pushing games of chance, leading to gambling in online platforms under the guise of gaming, which will harm the country’s youth, leading to addiction and financial debts. Furthermore, the distinction between the game of skill and chance is necessary as the inclusion of the game of chance would lead to gambling which is a State subject, and would further lead to the filing of cases under the provisions governing online gaming and gambling of respective States. In such a scenario, the rules would lead to chaotic situations instead of providing a unified regulatory mechanism, thereby defeating its intent and purpose. As the gaming industry in India continues to thrive, with a growing number of online gaming platforms and eSports tournaments being held in the country, it remains to be seen how the legal landscape for online gaming in India will evolve in the coming years. Nevertheless, if India wants to project itself as a global leader in the gaming industry, uniform legislation to regulate online gaming is indispensable.